As a provider that is intimately involved in supporting IBD patients; I am often focused on the microbiome balancing act. We just don’t really know if dysbiosis is driver or consequence or “both” when related to IBD.

This peer-reviewed article attempts to answer it:

Khan I, Ullah N, Zha L, et al. Alteration of Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Cause or Consequence? IBD Treatment Targeting the Gut Microbiome. Pathogens. 2019;8(3):126. doi: 10.3390/pathogens803012

Study Summary

1. Study Objective

This review explores whether gut microbiota alterations (dysbiosis) are a cause or a consequence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It also evaluates current and emerging therapeutic strategies targeting the microbiome.

2. Key Takeaway

Although a consistent pattern of dysbiosis is seen in IBD, a direct causal role remains unclear. Microbiome-directed therapies show potential benefits in modulating inflammation and maintaining remission.

3. Design

Narrative review of human and animal research studies, including clinical trials and mechanistic mouse models.

4. Participants

Studies cited include human patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), as well as genetically modified and germ-free mice used in colitis models.

5. Interventions

The paper reviews non-pharmaceutical interventions, including:

Prebiotics (e.g., inulin, germinated barley foodstuff)

Probiotics (e.g., Lactobacillus GG, E. coli Nissle 1917, VSL#3)

Synbiotics (e.g., Bifidobacterium longum with inulin)

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

6. Study Parameters Assessed

Markers of inflammation (CRP, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-alpha), microbial diversity (via sequencing), clinical symptoms (e.g., Disease Activity Index), and microbiota composition in fecal and mucosal samples.

7. Primary Outcome

To evaluate whether dysbiosis contributes to IBD pathogenesis and to assess the effectiveness of microbiome-targeting therapies.

8. Key Findings

Decreased diversity of beneficial microbes, such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Clostridium clusters, is common in IBD.

Genetic susceptibility (e.g., NOD2, ATG16L1) may impair microbial regulation and immune response. (

Prebiotics and probiotics improve select clinical and immune parameters in some patients.

FMT has shown inconsistent benefits in clinical trials.

9. Transparency

Funded by Chinese and provincial science agencies. No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Practice Implications and Limitations

The Khan et al. review provides a comprehensive synthesis of microbiota-based findings in IBD. For clinicians, the following insights are particularly relevant.

Dysbiosis Is an Associated Biomarker, Not a Proven Cause

Though dysbiosis is a reliable marker of IBD status, a direct causal role remains unproven. The observed reduction in microbial diversity, especially in Firmicutes and SCFA producers like F. prausnitzii, correlates with disease activity but may not initiate disease. Experimental models suggest that microbial imbalance contributes to inflammation in genetically susceptible hosts, but human studies are not yet definitive.

> Microbiome analysis may be helpful for monitoring disease progression or therapeutic response, but should not yet guide primary diagnosis or treatment alone.

Microbiome-Targeted Therapies Are Emerging

Probiotics such as VSL#3 and prebiotics like inulin and germinated barley foodstuff (GBF) have demonstrated mild-to-moderate success in maintaining remission or reducing inflammation in UC.

Synbiotics show enhanced efficacy in small studies. However, dosing, strain specificity, and patient response vary widely. FMT remains a promising but inconsistent intervention, likely influenced by donor-recipient microbiome compatibility and engraftment dynamics.

Host Genetics Influence the Microbiota-Immune Dialogue

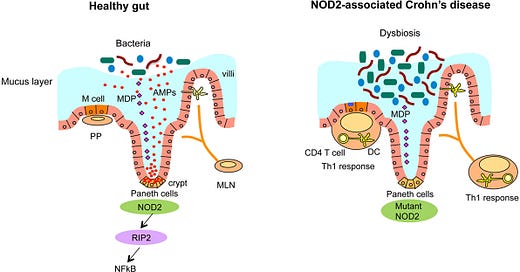

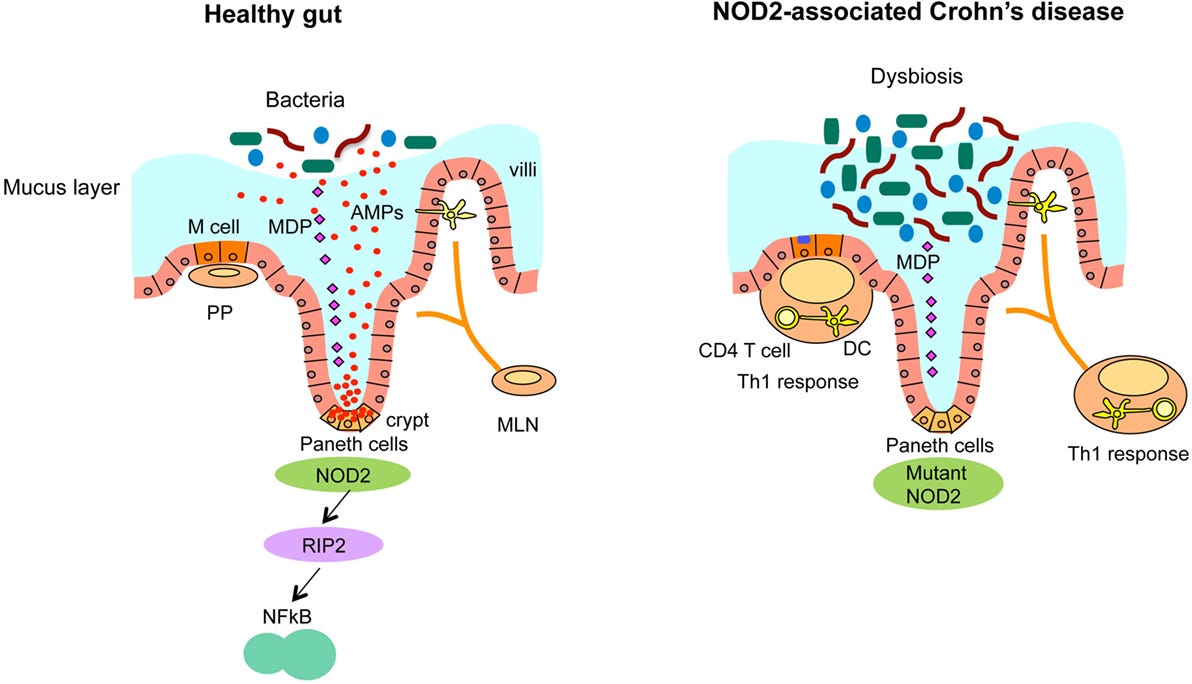

The review highlights how genetic variations, particularly NOD2 and ATG16L1 polymorphisms, affect microbial recognition and tolerance. These alterations may impair Paneth cell function, antimicrobial peptide production, and Treg induction, contributing to chronic inflammation. Therapies that enhance immune-microbial tolerance may be a fruitful path forward.

Impairment of NOD2 (nucleotide oligomerization domain 2 receptor) is a risk factor for dysbiosis, as this receptor interacts with the immune system to dampen inflammation and immune response. This is because NOD2 is a pattern recognition receptor involved in detecting muramyl dipeptide (MDP), a component of bacterial peptidoglycan. It plays a regulatory role in the innate immune response, especially in intestinal epithelial cells and Paneth cells. NOD2 mutations (loss-of-function) are associated with impaired microbial recognition, reduced antimicrobial peptide production, and increased risk for dysbiosis and Crohn’s disease.

Specific postbiotics, such as muropeptides, interact with innate immune receptors (NOD1/NOD2) to help mitigate inflammation, particularly in conditions like Crohn's disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Researchers are studying Heat-killed Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium lysates that may act like muropeptides.

From: Sidiq, T., Yoshihama, S., Downs, I., & Kobayashi, K. S. (2016). Nod2: a critical regulator of ileal microbiota and Crohn’s disease. Frontiers in Immunology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00367

NOD2 ; Through the innate immune system, NOD2 provides a defensive strategy to protect the host against bacterial infection. A mutated NOD2 has less protection against bacterial invasion.

from: Dowdell AS, Colgan SP. Metabolic Host–Microbiota Interactions in Autophagy and the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). Pharmaceuticals. 2021; 14(8):708. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph1408070

Autophagy-related genes (ATG16L1) are involved in phagocytosis (aka eating) bacteria that are invading the mucus wall. ATG16L1 are recruited by NOD2 to help with the protection and defense of bacterial invasion that slips past the mucus barrier. This is another vulnerability in IBD that predisposes dysbiosis. When NOD2 detects bacterial components, it helps recruit ATG16L1 to the site of invasion, triggering the gut's cellular "recycling system" to eliminate the threat. But in people with Crohn’s disease and other forms of IBD, this system often doesn’t work properly. Variants in ATG16L1 and NOD2 genes can impair this microbial clean-up process, allowing bacteria to persist in the gut lining, contributing to inflammation, dysbiosis, and ongoing immune activation.

Autophagy enhancers like spermidine, luteolin, and low-dose rapamycin may have a role here. I would like to let you know that there have not been robust human studies with my commentary of natural clinical applications.

Information for the Rest of Us

1. Herbal Immunomodulators:

Certain botanicals have shown the ability to modulate immune tone and support epithelial integrity in IBD models.

Astragalus polysaccharides improve the Th17/Treg balance and reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Curcumin inhibits NF-κB, enhances mucosal healing, and may match mesalamine in efficacy. (Don’t get ideas that it can replace it though without discussion with your GI team)

Andrographis, Boswellia, and Berberine exhibit anti-inflammatory effects.

While many herbal formulas still need rigorous RCT validation, the mechanistic promise especially in modulating barrier function and cytokine signaling is compelling.

2. Postbiotics

Postbiotics are non-viable bacterial components or metabolites think of them as the "whispers" microbes use to communicate with your immune system.

Muramyl dipeptide (MDP) and related muropeptides signal through NOD2, a receptor often impaired in Crohn’s disease. As mentioned above, drugs are in development, but Heat-killed probiotics (paraprobiotics) and bacterial cell wall extracts are being explored for their immune-modulating potential/NOD2 effect without colonization risk.

These compounds can modulate inflammation via NF-κB pathways, enhance IL-10, and promote Treg cell formation ;actions highly relevant in IBD.

3. SCFA Enhancers: Feeding the Gut From the Inside Out

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), especially butyrate, are critical for colonocyte health and inflammation resolution.

Prebiotic fibers like inulin, germinated barley foodstuff (GBF), and resistant starch have been shown to:

Increase butyrate production

Enhance epithelial barrier integrity

Reduce fecal calprotectin and CRP

While many commercial prebiotics focus on general gut wellness, these specific fibers are showing targeted benefits in IBD trials.

4. Mucosal Immune-Supportive Interventions

Supporting the gut’s structural defenses is just as crucial as tuning its microbial content.

Glutamine and zinc are essential for maintaining tight junction integrity.

EGCG (from green tea) and polyphenols support mucin production and reduce oxidative stress.

These interventions fortify the frontline mucosal defenses, potentially reducing the need for repeated microbial reseeding.

5. Autophagy Enhancers: Unlocking the Cell’s Cleanup Crew

Autophagy, the cellular process of “self-cleaning,” is dysregulated in many IBD patients; especially those with ATG16L1 polymorphisms.

Emerging compounds that may support autophagic pathways include:

Spermidine: Naturally occurring polyamine that enhances autophagy via EP300 inhibition. Shown to protect barrier function in colitis models.

Luteolin: A flavonoid that activates AMPK and inhibits mTOR/NF-κB, improving inflammation and autophagy markers in animal models.

Low-dose rapamycin: mTOR inhibitor with case series support in refractory Crohn’s. Promising but carries immunosuppressive risks.

These agents may eventually offer a precision medicine approach for patients with genetic or functional impairments in autophagy.

Final Thoughts

The future of IBD therapy may not rely solely on transplanting or feeding microbes. Instead, we are beginning to recognize the importance of host–microbe signaling, immune tolerance, and cellular housekeeping mechanisms like autophagy.

While much of this work is still in early stages, the convergence of herbal medicine, postbiotics, and nutrient signaling offers a therapeutic frontier that aligns with both systems biology and functional medicine.

If we can support the gut without always needing to change its residents, we may finally be on the path to sustainable, individualized remission.

Your turn

Have you addressed Dysbiosis and seen it help your overall management of IBD? What tests are you using to assess for dysbiosis? please comment below.